E

R

I

C

R

U

S

C

H

M

A

N

E

R

I

C

R

U

S

C

H

M

A

N

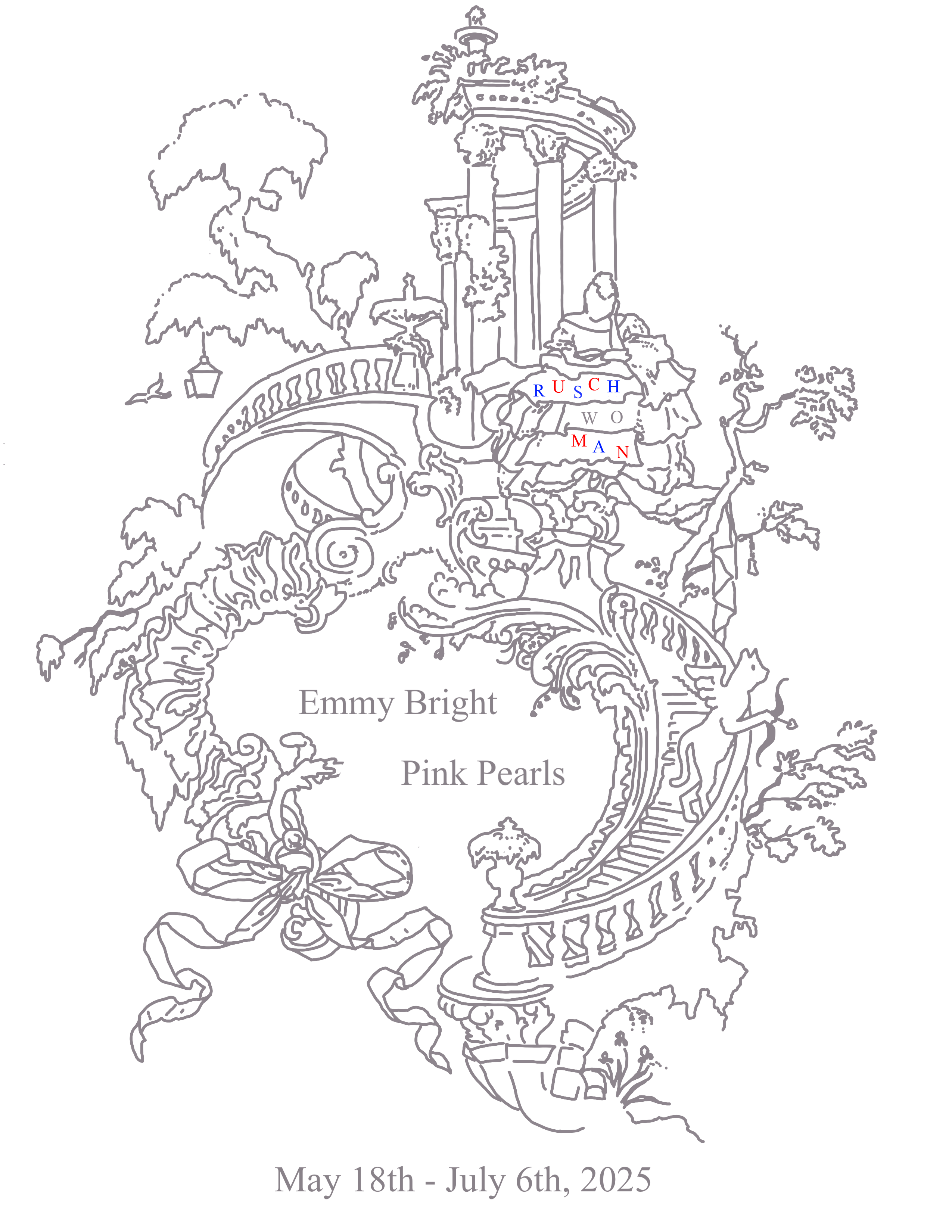

Emmy Bright

Pink Pearls

RUSCHWOMAN

May 18 — July 6, 2025

Opening Reception: Sunday, May 18, from 3–6PM

Outside of the Opening, gallery hours are available by appointment only.

Please contact thewaves@ruschwoman.blue to make arrangements

to visit RUSCHWOMAN during the run of the exhibition.

31.

…and lovely laughing—oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

I seem to me…

46.

and I on a soft pillow

will lay down my limbs

–Sappho. If not, winter. Translated by Anne Carson

Eros, freed from surplus-repression, would be strengthened, and the strengthened Eros would, as it were, absorb the objective

of the death instinct…In a repressive civilization, death itself becomes an instrument of repression.

–Herbert Marcuse. Eros and Civilization, 1956.

Pynk like the inside of your, baby (we're all just pynk)

Pynk like the walls and the doors, maybe (deep inside, we're all just pynk)

Pynk like your fingers in my, maybe

Pynk is the truth you can't hide

–Janelle Monáe. “Pynk.” Dirty Computer.

Bad Boy Records, 2018.

When butches cry

they weep, they wail,

they gnash their teeth

and moan

Strong woman’s pain

it’s just the same

except it’s mostly done

alone.

–Bonni Barringer. “When butches cry.”

The Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader.

Ed. Joan Nestle. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1992.

Emmy Bright’s new solo exhibition Pink Pearls is the grave site of Alice B. Toklas on the reverse side of Gertrude

Stein’s headstone in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. It’s the spot where a lip curls into the dark wet backside of itself

in a mouth. It’s an exit wound. It’s cream cheese icing on red velvet cake; it’s rosacea on the face of the culture wars storming

around us. It’s heartfelt and full of heart.

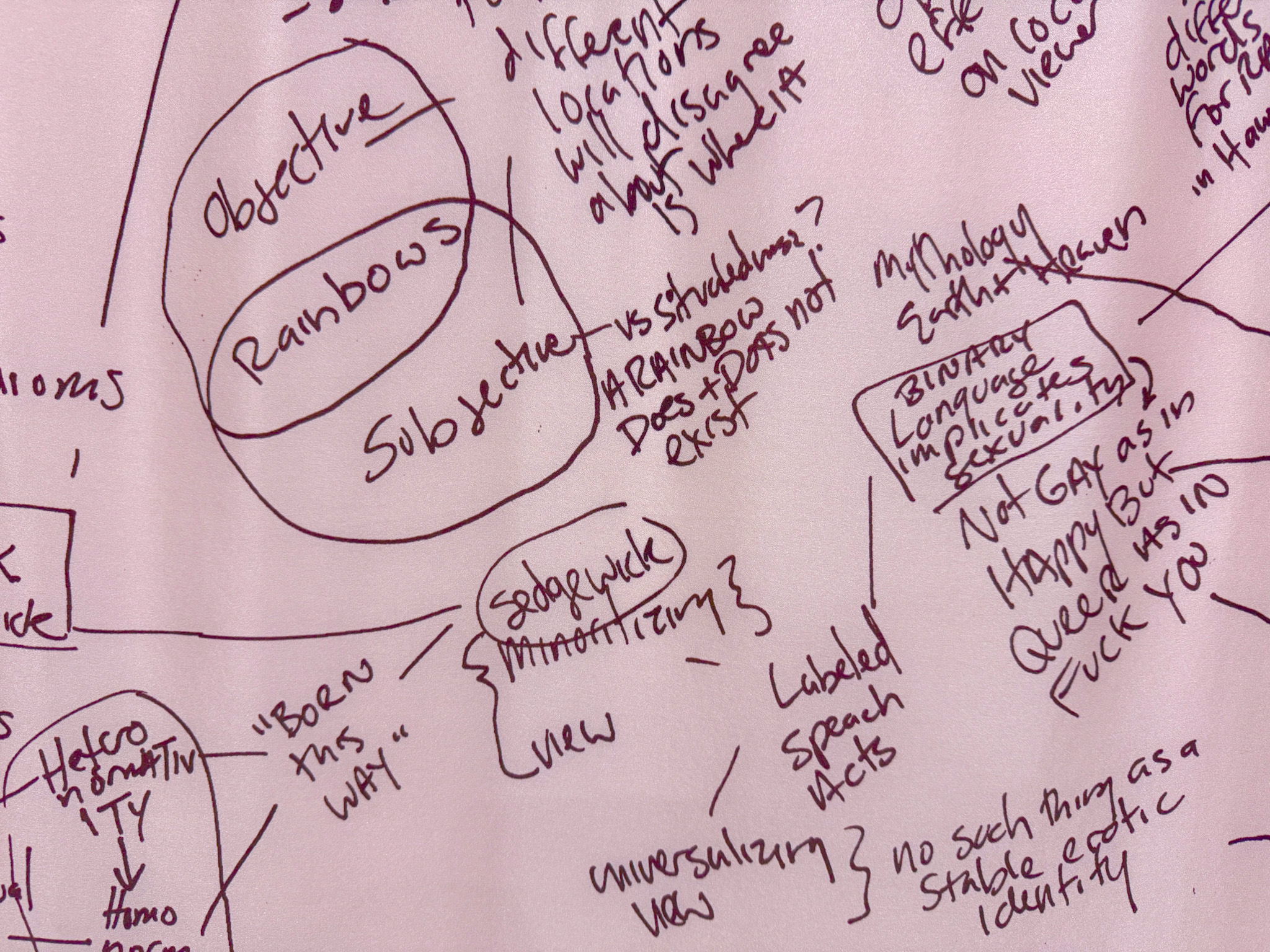

Bright provides tough, existential questions with material stakes, orienting a panoply of mediums toward inquiries and analyses

that are as squishy and mutable as they are pluralistic and galvanized by their own doubts, loopholes, and queernesses. For the

better part of a couple of decades, Bright has skittered along the structural limits (and breaches and excesses) of language,

affect, and an ethics of living with prints, publications, performances, objects, drawings, collages, quilts, and installations

that lend seductive formal refinement to performative comedy-tragedies. Moody and ebullient, hers is a practice of aching

disclosures that shatter heterosexist mores and the rigidity of public/private spheres maintained by capitalist notions of

ownership, gender norms, and repressive shame.

Amid neo-punk confessional scrawls, flurries of annotations and speculations, and hurly-burly affectations, Bright frequently

compliments blunt efficiencies of form and concept with tender gestures relaxed into softness. Against the nullifying directives

that ego must be reproduced (biologically, among other impulses) in order to establish meaning, Bright proliferates modes of care

expressed and received that have sustained queer lives for generations—an emboldened capacity for love in the face of social and

political forces that would deploy linguistic turns, legislative mandates, and threats of violence that would seek to annihilate

the possibilities of queer existence outright. But as butches and femmes, radical faeries, lesbian separatists, radical lesbian

feminists, friends of Dorothy, kings, queens, crips, NBs, trans dolls and dudes, and a problematic rainbow of other

positionalities demonstrate, we persist, reified through the invocations of us in their rejections, plotted into their metadata

and AI learning models, through their own absolute failures to act only within the bounds of the normative categories they

espouse.

Forms of love: pockets full of posies, pairs of pebbles, puppy bellies, poetry, mementos (and their goth sisters, memento mori),

mix tapes, melancholy, relics, remembrances, camp connoisseurship and the drive to collect, humor, horror, hysteria, hamfisted

hijinks, diaries, whimsy, what all is revealed by one’s preferred flavors of jelly beans, blood, sweat, tears (see also: big gay),

gore, an intentional divestment from discrete monolithic notions of selfhood.

When RUSCHWOMAN invited Emmy Bright to gather up some of the soft pink things that have made appearances in the work, none of us

knew that beneath those blushing cheeks (and sheets, and ceramic trays, and metal casts) would be LOVE and DEATH, those most

crucial of cultural underpinnings, those most emo and most urgent of tropes by which we understand our own existences. The stakes

are high; the gestures are flouncy; the posturing is in repose. In a rhapsody of pleasure-principle-death-drive upset, this

promiscuous body of work keeps it together—integrating contradiction, pink-eraser erasing divisions, riding away into the sunset

on proposals for unending questioning.

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, I Tried, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, found pink balloon, 6 1/2h x 5w in.

Emmy Bright, I Tried, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, found pink balloon, 6 1/2h x 5w in.

Emmy Bright, Benefit, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, little pouch, 9h x 10 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Benefit, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, little pouch, 9h x 10 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Habit No. 1 Tape No. 3, 2025, Ceramic, paint, found tape, 7h x 8 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Habit No. 1 Tape No. 3, 2025, Ceramic, paint, found tape, 7h x 8 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Keep It Together, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink pouch found in an alley, 15h x 13 1/4w in.

Emmy Bright, Keep It Together, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink pouch found in an alley, 15h x 13 1/4w in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Flower, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink flower drifted out from a local cemetery, 11 1/2h x 9w in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Flower, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink flower drifted out from a local cemetery, 11 1/2h x 9w in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, 2025, Ceramic, glaze, Pink Pearl tired erasers, 7 1/2h x 11w in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, 2025, Ceramic, glaze, Pink Pearl tired erasers, 7 1/2h x 11w in.

Emmy Bright, Freedom Song, 2024, Ceramic, glaze, chewed and pink dog leash, 13 1/4h x 10 1/4w in.

Emmy Bright, Freedom Song, 2024, Ceramic, glaze, chewed and pink dog leash, 13 1/4h x 10 1/4w in.

Emmy Bright, "Happy" Valentines Day, 2024, Ceramic, glaze, crumpled balloon, 22 1/2h x 16 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, "Happy" Valentines Day, 2024, Ceramic, glaze, crumpled balloon, 22 1/2h x 16 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Small Butch Flower, 2025, Cast iron, 3h x 7w x 2d in.

Emmy Bright, Two Lips, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink bouquet drifted out from a local cemetery, 18 1/2h x 10w in.

Emmy Bright, Two Lips, 2023, Ceramic, glaze, pink bouquet drifted out from a local cemetery, 18 1/2h x 10w in.

Emmy Bright, Big Butch Flower, 2025, Ceramic, glaze, 5h x 18w x 7d in.

Emmy Bright, Big Butch Flower, 2025, Ceramic, glaze, 5h x 18w x 7d in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Rainbow Problems: Is it a thing?, 2023, Digitally printed satin, grommets, 54h x 104 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Rainbow Problems: Is it a thing?, 2023, Detail View

Emmy Bright, Rainbow Problems: Is it a thing?, 2023, Detail View

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Perfect Lovers from Another Mother (after FGT), 2024, Ceramic, paint, rocks found outside my dog's physical therapy office, 6h x 9 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Perfect Lovers from Another Mother (after FGT), 2024, Ceramic, paint, rocks found outside my dog's physical therapy office, 6h x 9 1/2w in.

Emmy Bright, Pink Pearls, Installation View

Emmy Bright, Crying, 2023, Ceramic, paint, glaze, pump, blue water, 7 1/2h x 10 1/2w x 12 1/2d in.

Emmy Bright, Crying, 2023, Ceramic, paint, glaze, pump, blue water, 7 1/2h x 10 1/2w x 12 1/2d in.